Школьная энциклопедия

Содержание:

История

Яцек Тылицки, Каменная скульптура, Apaмбол джунгли, Гоа, Индия,

Французский художник Марсель Дюшан подготовил «почву» для концептуалистов своими реди-мейдами. Наиболее известным из дюшановских реди-мейдов был «Фонтан» (1917), писсуар, подписанный художником псевдонимом «R.Mutt» (каламбур, напоминавший о популярных мультяшных героях Матте и Джеффе), и предложенный в качестве экспоната для выставки Общества независимых художников Нью-Йорка. В традиционном понимании, обычный предмет не мог быть искусством, потому что не сделан художником, не уникален, и обладает немногими эстетическими достоинствами традиционного, сделанного вручную художественного объекта

Идеи Дюшана и их теоретическая важность для будущего концептуализма было позднее оценено американским художником Джозефом Кошутом. В своём эссе «Искусство после философии» (Art after Philosophy, 1969) Кошут писал: «Все искусство (после Дюшана) — концептуально по своей природе, потому что искусство и существует лишь в виде идеи» («All art (after Duchamp) is conceptual (in nature) because art only exists conceptually»)

Концептуальное искусство оформилось как движение на протяжении 1960-х. В 1970 состоялась первая выставка концептуального искусства Концептуальное искусство и концептуальные художники, которая была проведена в Нью-Йоркском культурном центре.

Изобретение термина «концептуальное искусство» приписывают американскому философу и музыканту Генри Флинту. Так называлось его эссе 1961 года (Conceptual Art), опубликованное в книге An Anthology of Chance Operations под редакцией Джексона МакЛоу и Ла Монте Янга в 1963 году.

Life

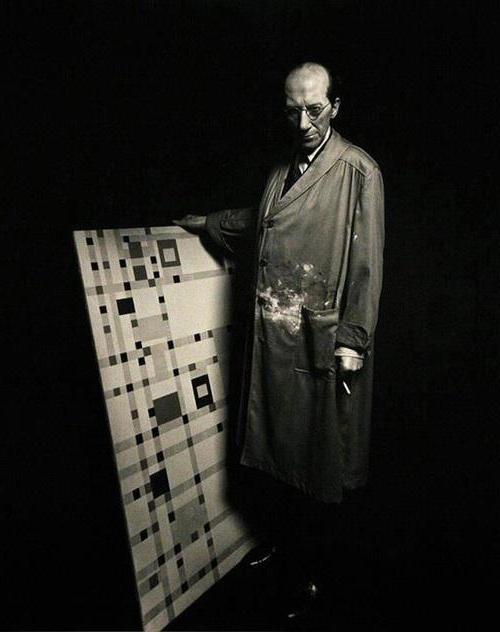

Sol LeWitt, Untitled lithograph 1992

LeWitt was born in Hartford, Connecticut to a family of Jewish immigrants from Russia. His mother took him to art classes at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford. After receiving a BFA from Syracuse University in 1949, LeWitt traveled to Europe where he was exposed to Old Master paintings. Shortly thereafter, he served in the Korean War, first in California, then Japan, and finally Korea. LeWitt moved to New York City in 1953 and set up a studio on the Lower East Side, in the old Ashkenazi Jewish settlement on Hester Street. During this time he studied at the School of Visual Arts while also pursuing his interest in design at Seventeen magazine, where he did paste-ups, mechanicals, and photostats. In 1955, he was a graphic designer in the office of architect I.M. Pei for a year. Around that time, LeWitt also discovered the work of the late 19th-century photographer Eadweard Muybridge, whose studies in sequence and locomotion were an early influence. These experiences, combined with an entry-level job as a night receptionist and clerk he took in 1960 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, would influence LeWitt’s later work.

At MoMA, LeWitt’s co-workers included fellow artists Robert Ryman, Dan Flavin, Gene Beery, and Robert Mangold, and the future art critic and writer, Lucy Lippard who worked as a page in the library. Curator Dorothy Canning Miller’s now famous 1960 «Sixteen Americans» exhibition with work by Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Frank Stella created a swell of excitement and discussion among the community of artists with whom LeWitt associated. LeWitt also became friends with Hanne Darboven, Eva Hesse, and Robert Smithson.

LeWitt taught at several New York schools, including New York University and the School of Visual Arts, during the late 1960s. In 1980, LeWitt left New York for Spoleto, Italy. After returning to the United States in the late 1980s, LeWitt made Chester, Connecticut, his primary residence. He died at age 78 in New York from cancer complications.

Influence

Black Form Dedicated to the Missing Jews, Altona City Hall, Altona, Hamburg, Germany, 1987.

Sol LeWitt was one of the main figures of his time; he transformed the process of art-making by questioning the fundamental relationship between an idea, the subjectivity of the artist, and the artwork a given idea might produce. While many artists were challenging modern conceptions of originality, authorship, and artistic genius in the 1960s, LeWitt denied that approaches such as Minimalism, Conceptualism, and Process Art were merely technical or illustrative of philosophy. In his Paragraphs on Conceptual Art, LeWitt asserted that Conceptual art was neither mathematical nor intellectual but intuitive, given that the complexity inherent to transforming an idea into a work of art was fraught with contingencies. LeWitt’s art is not about the singular hand of the artist; it is the idea behind each work that surpasses the work itself. In the early 21st century, LeWitt’s work, especially the wall drawings, has been critically acclaimed for its economic perspicacity. Though modest—most exist as simple instructions on a sheet of paper—the drawings can be made again and again and again, anywhere in the world, without the artist needing to be involved in their production.

Summary of Sol LeWitt

Sol LeWitt earned a place in the history of art for his leading role in the Conceptual movement. His belief in the artist as a generator of ideas was instrumental in the transition from the modern to the postmodern era. Conceptual art, expounded by LeWitt as an intellectual, pragmatic act, added a new dimension to the artist’s role that was distinctly separate from the romantic nature of Abstract Expressionism. LeWitt believed the idea itself could be the work of art, and maintained that, like an architect who creates a blueprint for a building and then turns the project over to a construction crew, an artist should be able to conceive of a work and then either delegate its actual production to others or perhaps even never make it at all. LeWitt’s work ranged from sculpture, painting, and drawing to almost exclusively conceptual pieces that existed only as ideas or elements of the artistic process itself.

Примечания

- ↑ Уилл Гомперц. Непонятное искусство. От Моне до Бэнкси.. — Москва: Синдбад, 2018. — С. 357. — 464 с. — ISBN 978-5-906837-42-4.

- ↑ Сергей Гущин, Александр Щуренков. Современное искусство и как перестать его бояться.. — Москва: АСТ, 2018. — С. 182-183. — 240 с. — ISBN 978-5-17-109039-5.

- Сьюзи Ходж. Главное в истории искусств. Ключевые работы, темы, направления, техники. / Ольга Киселева. — Москва: Манн, Иванов и Фербер, 2018. — С. 47. — 224 с. — ISBN 978-5-00117-015-0.

- Tony Godfrey, Conceptual Art, London: 1998. p. 28

- Уилл Гомприц. Непонятное искусство. От Моне до Бэнкси.. — Москва: Синдбад, 2018. — С. 23. — 464 с. — ISBN 978-5-906837-42-4.

- ↑ Антон Хитров. . The Village (14.12.16).

- NoFavorite. (англ.). christojeanneclaude.net. Дата обращения 27 сентября 2018.

- .

- .

- Konzeptkunst (нем.) // Wikipedia. — 2019-02-10.

Museum collections

LeWitt’s works are found in the most important museum collections including: Tate Modern, London, the Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, National Museum of Serbia in Belgrade, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, Hallen für Neue Kunst Schaffhausen, Switzerland, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, Australia, Guggenheim Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Dia:Beacon, The Jewish Museum in Manhattan, MASS MoCA, North Adams, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. The erection of Double Negative Pyramid by Sol LeWitt at Europos Parkas in Vilnius, Lithuania was a significant event in the history of art in post Berlin Wall era.

Important Art by Sol LeWitt

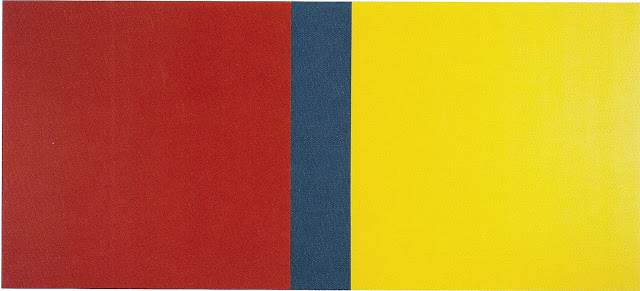

LeWitt used traditional materials-oil and pigment on wood-when he produced Wall Structure Blue. The format, a colorful square within the framework of a larger square, imitates traditional painting with the red bulls-eye in the center calling attention to an imagined narrative and to the symmetry imposed by convention. The simple, yet striking square set in the middle of the canvas is reminiscent of Jasper Johns’ handling of the target pieces, which LeWitt had seen at an exhibition at MoMA around the time he produced Wall Structure Blue. This Minimalist painting marks a definitive break with LeWitt’s earlier body of work, which still made use of language and form-from the human figure to simplified, abstract objects.

Derived from the spare, iconic forms that began with such paintings as Wall Structure Blue, this work stands as their most elemental component. Although the shape is abstract, the relatable, human-like proportions (it stands 96 inches high) recall a skeleton, with all of its solemn dignity and shock value. As one of the first open structures, Standing Open Structure Black can be seen as the standard building block for much of LeWitt’s later work. As with his Minimalist painting, LeWitt’s simplified sculptures of this period challenge the notion of completeness and suggest that any additions to the basic elements of a work of art are excessive.

This accumulation of open structures signifies a revival of seriality in LeWitt’s work, inspired by the serial photographs of Eadweard Muybridge, whose work LeWitt discovered in an abandoned book a previous tenant had left in his apartment. The network of cubes allowed LeWitt to study the juxtaposition of different sizes and shapes, arranged according to certain preset rules and ideas. Looking at Serial Project #1 as a whole, it appears to be nothing so much as a city, revealing LeWitt’s architectural roots. It also imposes itself as a kind of framework for a finished work or series of works, imitating the preparatory sketches that precede blueprints and completed structures. Once again, LeWitt challenges the conventional methods of artistic production; in this instance, he halts the additive process of sculpting and allows the viewer to observe what would only have existed beneath other materials.

More Important Art

View all Important Art

История

Яцек Тылицки, Каменная скульптура, Apaмбол джунгли, Гоа, Индия,

Изобретение термина «концептуальное искусство» приписывают американскому философу и музыканту Генри Флинту. Так называлось его эссе 1961 года (Conceptual Art), опубликованное в книге An Anthology of Chance Operations под редакцией Джексона МакЛоу и Ла Монте Янга в 1963 году.

Французский художник Марсель Дюшан подготовил «почву» для концептуалистов своими «реди-мейдами». Наиболее известным из дюшановских реди-мейдов был «Фонтан» (1917), писсуар, подписанный художником псевдонимом «R.Mutt» (каламбур, напоминавший о популярных мультяшных героях Матте и Джеффе), и предложенный в качестве экспоната для выставки Общества независимых художников Нью-Йорка.

Именно М. Дюшан впервые поднял вопрос о переоценке того, что можно считать искусством. До этого момента считалось, что искусство должно обладать эстетической, технической и интеллектуальной ценностью

Идеи Дюшана и их теоретическая важность для будущего концептуализма было позднее оценено американским художником Джозефом Кошутом. В своём эссе «Искусство после философии» (Art after Philosophy, 1969) Кошут писал: «Все искусство (после Дюшана) — концептуально по своей природе, потому что искусство и существует лишь в виде идеи» («All art (after Duchamp) is conceptual (in nature) because art only exists conceptually»)

Исполнив провокационный и показательный разрыв с традицией в 1917 году, художник дает начало новой концепции, исходя из которой, идея и задумка автора при оценке произведения превосходят его зримую красоту.

Отстаивая первостепенность концепции над самим создаваемым объектом, он настаивал на том, что художников не следует ограничивать в выражении своих мыслей и эмоций. Теперь художник в праве передать свою идею теми средствами, которыми тот посчитает нужными. Как вариант, идея может быть передана даже посредством собственного тела, в субжанре концептуального искусства, который получил название «перфоманс».

В узком смысле слова термин «концептуализм» связан с художниками второй половины 1960-х годов, задавшихся вопрос о том, что есть искусство (art in general). Одним из главных инструментов в концептуальном искусстве 1960-х годов становится фотография. С помощь камеры удается провести некоторый анализ. Например, французская художница Софи Калль с помощью фотографии выявляет фиктивность любого документа. Также отметим советского фотографа Бориса Михайлова, единственного фотографа из СССР, у которого была своя ретроспектива в Музее современного искусства в Нью-Йорке.

Концептуальное искусство оформилось как движение на протяжении всего периода 1960-х. В 1970 состоялась первая выставка концептуального искусства Концептуальное искусство и концептуальные художники, которая была проведена в Нью-Йоркском культурном центре.

НАШИ ЛЮДИ

JWoww

Живопись

американская художница

JR (художник)

Живопись

это флайпостинг больших черно-белых изображений в публичных местах, в манере освоения антропогенной среды граффити-художниками

Alva Noto

Живопись

сценическое имя звукового художника Карстена Николая , работающего в стилях экспериментальной электронной музыки , одного из основателей лейбла raster-noton

Яшке, Владимир Евгеньевич

Живопись

российский художник и поэт

Яшвиль, Наталья Григорьевна

Живопись

русская художница и общественная деятельница

Яхилевич, Михаил Фритиофович

Живопись

российский и израильский художник, дизайнер, художник сцены

Ясуи, Сотаро

Живопись

японский художник

Ясновский, Фёдор Иванович

Живопись

русский художник-пейзажист, мастер акварели

Selected books

Four-Sided Pyramid, National Gallery of Art

- Bloom, Lary. Sol LeWitt: A Life of Ideas, Wesleyan University Press, 2019. (ISBN 978-0-8195-7868-6)

- LeWitt, Sol. Arcs, from Corners & Sides, Circles, & Grids and All Their Combinations. Bern, Switzerland: Kunsthalle Bern & Paul Biancini, 1972.

- LeWitt, Sol. The Location of Eight Points. Washington, DC: Max Protetch Gallery, 1974.

- LeWitt, Sol. Photogrids. New York: P. David Press, 1977/1978. ISBN 0-8478-0166-7

- Legg, Alicia (ed.). Sol LeWitt: the Museum of Modern Art, New York. New York: The Museum, 1978. ISBN 0-87070-427-3

- LeWitt, Sol. Geometric Figures & Color. New York: H.N. Abrams, 1979. ISBN 0-8109-0953-7

- LeWitt, Sol. Autobiography. New York and Boston: Multiple and Lois and Michael K. Torf, 1980. ISBN 0-9605580-0-4

- LeWitt, Sol. Sol LeWitt Wall Drawings, 1968-1984. ISBN 90-70149-09-5

- LeWitt, Sol. Sol LeWitt Prints, 1970-86. London: Tate Gallery, 1986. ISBN 0-946590-51-6

- LeWitt, Sol. Sol LeWitt Drawings, 1958-1992. The Hague: Haags Gemeentemuseum, 1992. ISBN 90-6730-092-6

- LeWitt, Sol. Sol LeWitt, Twenty-Five Years of Wall Drawings, 1968-1993. Andover, MA, and Seattle: Addison Gallery of American Art and University of Washington Press, 1993. ISBN 1-879886-34-0

- LeWitt, Sol. Sol LeWitt — Structures, 1962-1993. Oxford: Museum of Modern Art, 1993. ISBN 0-905836-78-2

- LeWitt, Sol, Cristina Bechtler, and Charlotte von Koerber. 100 Cubes. Ostfildern: Cantz, 1996. ISBN 3-89322-753-9

- LeWitt, Sol. Sol LeWitt, Bands of Color. Chicago: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1999. ISBN 0-933856-58-X

- Garrels, Gary, and Sol LeWitt. Sol LeWitt: a Retrospective. San Francisco and New Haven: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and Yale University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-300-08358-0

- Gale, Peggy (ed.). Artists Talk: 1969–1977. Halifax, NS: Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 2001. ISBN 0-919616-40-2

- LeWitt, Sol, Nicholas Baume, Jonathan Flatley, and Pamela M. Lee. Sol LeWitt: Incomplete Open Cubes. Hartford, CT, and Cambridge, MA: Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art and MIT Press, 2001. ISBN 0-262-52311-6

- LeWitt, Sol, Dean Swanson, and Martin L. Friedman. LeWitt x 2: Sol LeWitt: Structure and Line: Selections from the LeWitt Collection. Madison, WI: Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, 2006. ISBN 0-913883-33-6

- LeWitt, Sol. Sol LeWitt: Wall Drawings. Bologna, Italy: Damiani, 2006. ISBN 88-89431-59-8

- Cross, Susan, and Denise Markonish (eds.). Sol LeWitt: 100 Views. North Adams, MA, and New Haven, CT: Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art and Yale University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-300-15282-1

- Maffei, Giorgio, and Emanuele De Donno. Sol LeWitt: Artist’s Books. Sant’Eraclio di Foligno, Italy: Viaindustriae, 2009. ISBN 978-88-903459-2-0

- LINES & FORMES (sic), Livre d’artiste (album de douze planches en noir et blanc), édité par YVON LAMBERT, Paris 1989, ISBN 978-2-900982-06-8.

- Roberts, Veronica (ed.), Lucy R. Lippard, and Kirsten Swenson. «Converging Lines: Eva Hesse and Sol LeWitt.» Austin: Blanton Museum of Art. Distributed by Yale University Press, 2014. ISBN 0-300-20482-5

История минимализма

Считается, что минимализм стал продолжением фумизма (фюмизма). Фумизм – условно-декадентское течение в парижском искусстве, существовавшее с конца 70-х годов XIX в. до первой четверти XX в. Или же можно сказать наоборот: фумизм – предтеча минимализма. Основателями и идейными вдохновителями течения были Эмиль Гудо (поэт, писатель, чиновник министерства финансов и основатель «Общества Гидропатов»), а также Альфонс Алле (французский журналист, эксцентричный писатель и чёрный юморист, известный своим острым языком и мрачными абсурдистскими выходками). В краткой форме фумизм можно охарактеризовать как «искусство пускать дым в глаза», – практически, то же самое, что дадаизм, только на сорок лет раньше.Термин «фумизм» образован из существительного fumée (фр.) – дым. Это философский термин, обозначающий отношение человека к миру, самому себе, а также к искусству. Новое отношение выражалось в намеренном осмеянии и высмеивании всего и вся без каких бы то ни было ограничений и запретов, посрамлении обыденного скудоумия и бюргерского сознания. Чем непонятнее и абсурднее, чем сильнее недоумение, тем лучше и выше результат – таков был идейный девиз фумистов.Какие свойства должнó иметь эстетическое течение (или стиль), основа которого – «дым»? «Толковый словарь» Ожегова одно толкование этого слова: «дым – летучие продукты горения с мелкими частицами угля». Устойчивые выражения: «Густой дым. Нет дыма без огня. Дым коромыслом. Поругаться в дым. Дымовая завеса». Но во французском языке слово fumée и производные от него, а также созвучные имеют больше значений: собственно дым и курение, печники, трубочисты, болтуны, лжецы, пустомели.

Альфонс Алле «Битва негров в глубокой пещере тёмной ночью» (1882)Исходя из этого, можно сказать следующее: как пускается дым в глаза, так розыгрыши и глумления распространились по всему Парижу, а затем и дальше в форме фумизма. А из фумизма вышел дадаизм и в дальнейшем сюрреализм.

- < Назад

- Вперёд >