Дюбюффе, жан

Содержание:

- Европейские коллекции

- Литература

- Notes

- Transition to Art Brut

- Important Art by Jean Dubuffet

- Література[ред. | ред. код]

- ТВОРЧЕСТВО

- Литература

- Литература[править | править код]

- Artistic style

- Accomplishments

- Early work

- БИБЛИОГРАФИЯ

- Summary of Jean Dubuffet

- БИОГРАФИЯ ХУДОЖНИКА

- Литература

- Виставки[ред. | ред. код]

- Selected bibliography

- Біографія і творчість[ред. | ред. код]

Европейские коллекции

Бельгийский Музей доктора Гислена был основан в 1986 году как центр экспертизы лечения ментальных болезней. Музей располагается в здании первой бельгийской психиатрической клиники в Генте. В 2002 году сюда была передана голландская коллекция аутсайдерского искусства фонда Collectie de Stadshof (ранее Музей доктора Гислена работал только как музей истории психиатрии). Коллекция Стадсхоф собиралась на протяжении тридцати лет любителями «странного искусства» и к моменту передачи в Музей Гислена включала около 6000 произведений аутсайдерского, визионерского, наивного искусства порядка 400 авторов

Важно отметить, что экспозиции многих выставок музея построены по междисциплинарному принципу и сочетают в себе исторические предметы, искусство аутсайдеров и актуальное искусство

С.В. Гластра. Даниил во рву львином. 1965–1970. Лен, шелк, шерсть, вышивка. Музей доктора Гислена, Гент

Несмотря на потерю для Франции коллекции Жана Дюбюффе, там существует важная и очень логично сформированная публичная коллекция ар брюта. В 1999 году ассоциация L’Aracine передала в дар множество произведений ар брюта — рисунки, картины, коллекции, предметы и скульптуры более чем 170 французских и иностранных художников. В 2007 году для размещения этой исключительной коллекции было выделено отдельное крыло вновь построенного здания. Сегодня коллекция пополняется, организуется множество монографических или тематических выставок по всему миру. В коллекции LaM представлены знаковые для мира аутсайдерского искусства имена: Алоиз Корбац, Генри Дарджер, Огюстен Лесаж, Мишель Неджар, Андре Робийяр, Виллем ван Генк, Адольф Вёльфли и другие. Есть в коллекции и произведения русского аутсайдера Александра Лобанова. Сейчас коллекция насчитывает около 3500 произведений.

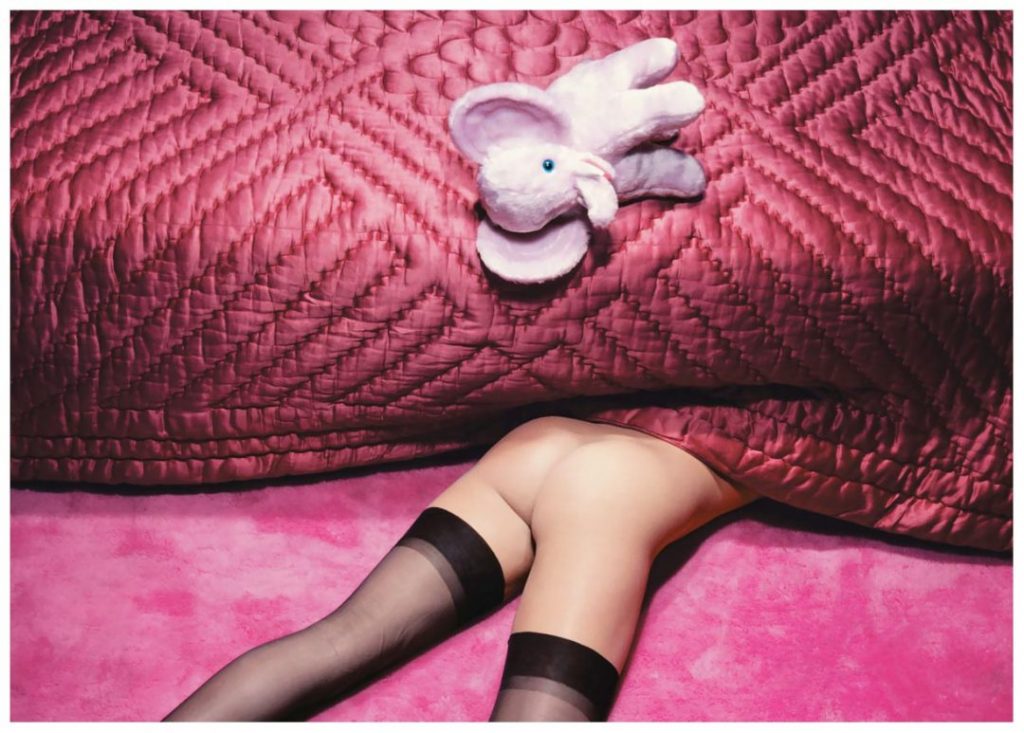

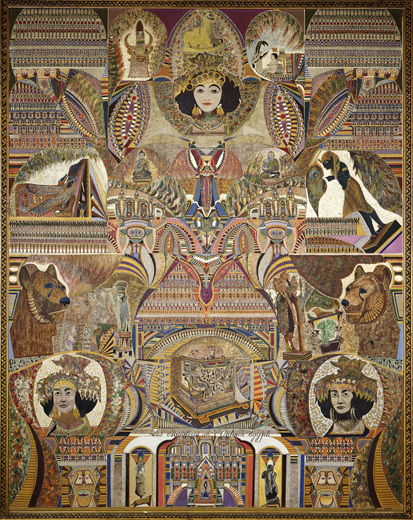

Огюстен Лесаж. Тайны Древнего Египта. 1930. Холст, масло. Музей метрополии Лилля. Adagp, Paris

Некоторые европейские коллекции и музеи аутсайдерского искусства имеют сложную, подчас трагическую историю. В 2006 году в пригороде Вены открылся Музей Гуггинг. История психиатрической клиники в коммуне Мария Гуггинг в Клостернойбурге в период нацизма была связана с нацистской программой принудительной эвтаназии, с ноября 1940 по май 1941 года 675 пациентов клиники были отправлены в центр принудительной эвтаназии под Линцем. После Второй мировой войны клиника продолжила работу, а инициатором формирования ее коллекции стал психиатр Лео Навратил (1921–2006), с конца 1950-х в диагностических целях привлекавший своих пациентов к рисованию и в 1965 году написавший книгу «Шизофрения и искусство». В 1981 году Навратил основал в клинике Центр искусства и психотерапии, который представлял собой одновременно жилой дом, художественную мастерскую и галерею. В 2006 году он стал музеем.

В 2009 году в Лондоне появился Музей всего. Сегодня коллекция этого частного музея, созданного британским куратором Джеймсом Бреттом, включает примерно 2000 произведений около 200 художников со всего мира. Уже через три года после своего создания Музей всего стал одной из знаковых институций аутсайдерского искусства XX — начала XXI века. Выставки его коллекции прошли в крупных музейных и выставочных институциях, в том числе в Тейт Модерн в Лондоне (2010), в Пинакотеке Аньелли в Турине (2010), в Hayward Gallery в Лондоне (2013), в Кунстхалле Роттердама (2016), Музее старого и нового искусства в Тасмании (2017–2018). В 2012 году Музей всего при поддержке Музея современного искусства (тогда Центра современной культуры) «Гараж» совершил поездки по крупным городам России (Санкт-Петербург, Нижний Новгород, Екатеринбург, Казань, Москва) и провел там крупные выставки-смотры регионального аутсайдерского искусства.

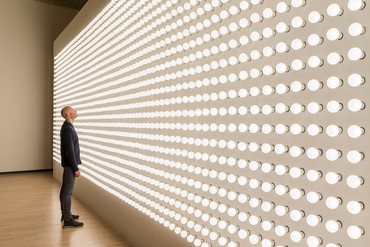

Проект «Музей всего» британского куратора Джеймса Бретта в России: поиск художников для «Выставки № 5» (представлена в Центре современной культуры «Гараж» в 2013 году). Courtesy Музей современного искусства «Гараж»

Литература

- Ragon M. Dubuffet. — N. Y.: Grove Press, 1959.

- Selz P. The Work of Jean Dubuffet. — N. Y.: The Museum of Modern Art, 1962.

- Loreau M. Jean Dubuffet, délits déportements lieux de haut jeu. — P.: Weber, 1971.

- Franzke A. Jean Dubuffet. — Basel: Beyeler, 1976.

- Thévoz M. Art brut. — N. Y.: Rizzoli, 1976.

- Thévoz M. Jean Dubuffet. — Genève: Albert Skira, 1986.

- Glimcher M. Jean Dubuffet: Towards an Alternative Reality. — N. Y.: Pace Gallery, 1987.

- Webel S. L’œuvre gravé et les livres illustrés par Jean Dubuffet: catalogue raisonné. — P.: Baudoin-Lebon, 1991.

- Haas M. Jean Dubuffet. — B.: Reimer, 1997.

- Lageira J. Jean Dubuffet, le monde de l’hourloupe. — P.: Gallimard; Centre Pompidou, 2001.

- Danchin L. Jean Dubuffet. — N. Y.: Vilo International, 2001.

- Bonnefoi G. Jean Dubuffet. Caylus: Association mouvements, 2002.

- Jean Dubuffet. Trace of an Adventure/ Ed. by Agnes Husslein-Arco. — Münch.: Prestel, 2003.

- Krajewski M. Jean Dubuffet. Studien zu seinem Fruehwerk und zur Vorgeschichte des Art brut. — Osnabrück: Der andere Verlag, 2004.

- Jacobi M. Jean Dubuffet et la fabrique du titre. — P.: CNRS, 2006.

Notes

- ^

- Colin-Picon, M., Georges Limbour: le songe autobiographique, Lachenal & Ritter, Paris, 1994. (Collection of letters between Limbour and Dubuffet, with biographical material.)

- ^ Selz, Peter. The Work of Jean Dubuffet, with Texts by the Artist. New York: New York Museum of Modern Art, 1962. Print.

- Kenneth Goldsmith, Duchamp Is My Lawyer: The Polemics, Pragmatics, and Poetics of UbuWeb, Columbia University Press, New York, pp. 238-240

- Colin-Picon, op. cit

- ^ D’Souza, Aruna. «I Think Your Work Looks A Lot Like Dubuffet: Dubuffet and America, 1946-1962». Oxford Art Journal 20.2 (1997): 61.

- D’Souza, Aruna. I Think Your Work Looks A Lot Like Dubuffet: Dubuffet and America, 1946-1962. Oxford Art Journal 20.2 (1997): 63.

- ^ Minturn, Kent. «Dubuffet, Levi-Strauss, and the Idea of Art Brut». Anthropology and Aesthetics 46 (2004): 247-258.

- Minturn, Kent. «Dubuffet, Levi-Strauss, and the Idea of Art Brut». Anthropology and Aesthetics 46 (2004): 248.

- Selz, Peter. The Work of Jean Dubuffet, with Texts by the Artist. New York: New York Museum of Modern Art, 1962. Print. Pg. 19

- California. University, Irvine. Art Gallery. Five Europeans: Bacon, Balthus, Dubuffet, Giacometti. Irvine: The Gallery, 1966. Print.

- Arts Council of Great Britain. Jean Dubuffet Drawings. London: Arts Council, 1966. Print.

- Dubuffet, Jean 1901-1985. Jean Dubuffet Paintings. London: Arts Council, 1966. Print.

Transition to Art Brut

Between 1947 and 1949, Dubuffet took three separate trips to Algeria—a French colony at the time—in order to find further artistic inspiration. In this sense, Dubuffet is very similar to other artists such as Delacroix, Matisse, and Fromentin. However, the art that Dubuffet produced while he was there was very specific insofar as it recalled Post-War French ethnography in light of decolonization. Dubuffet was fascinated by the nomadic nature of the tribes in Algeria—he admired the ephemeral quality of their existence, in that they did not stay in any one particular area for long, and were constantly shifting. The impermanence of this kind of movement attracted Dubuffet and became a facet of Art Brut. In June 1948, Dubuffet, along with Jean Paulhan, Andre Breton, Charles Ratton, Michel Tapie, and Henri-Pierre Roche, officially established La Compagnie de l’art brut in Paris. This association was dedicated to the discovery, documentation and exhibition of art brut. Dubuffet later amassed his own collection of such art, including artists such as Aloïse Corbaz and Adolf Wölfli. This collection is now housed at the Collection de l’art brut in Lausanne, Switzerland. His Art Brut collection is often referred to as a ‘museum without walls,’ as it transcended national and ethnic boundaries, and effectively broke down barriers between nationalities and cultures.

Influenced by Hans Prinzhorn’s book Artistry of the Mentally Ill, Dubuffet coined the term art brut (meaning «raw art,» often referred to as ‘outsider art’) for art produced by non-professionals working outside aesthetic norms, such as art by psychiatric patients, prisoners, and children. Dubuffet felt that the simple life of the everyday human being contained more art and poetry than did academic art, or great painting. He found the latter to be isolating, mundane, and pretentious, and wrote in his Prospectus aux amateurs de tout genre that his aim was ‘not the mere gratification of a handful of specialists, but rather the man in the street when he comes home from work….it is the man in the street whom I feel closest to, with whom I want to make friends and enter into confidence, and he is the one I want to please and enchant by means of my work.’ To that end, Dubuffet began to search for an art form in which everyone could participate and by which everyone could be entertained. He sought to create an art as free from intellectual concerns as Art Brut, and as a result, his work often appears primitive and childlike. His form is often compared to wall scratchings and children’s art. Nonetheless, Dubuffet appeared to be quite erudite when it came to writing about his own work. According to prominent art critic Hilton Kramer, «There is only one thing wrong with the essays Dubuffet has written on his own work: their dazzling intellectual finesse makes nonsense of his claim to a free and untutored primitivism. They show us a mandarin literary personality, full of chic phrases and up-to-date ideas, that is quite the opposite of the naive visionary.»

Important Art by Jean Dubuffet

The painting Apartment Houses, Paris focuses on urban life. The buildings are tilted, playfully defying architectural integrity. The flattening of the space between the sky, buildings, and civilians seems spontaneous and unprocessed — childlike. Here Dubuffet satirizes conventional, sentimental images of Paris, suggesting instead that the jollity of the city’s inhabitants is forced and false.

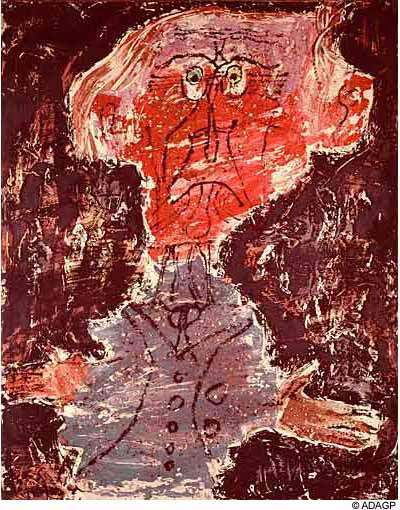

This picture is typical of the Hautes Pates series that Dubuffet exhibited to huge controversy in 1946. A thick, monochromatic surface serves as the ground for the crudely depicted figure, which is a parody of portraiture. Although Dubuffet undoubtedly intended the series to offend and his graphic style and thick, coarse impasto certainly did offend conventional tastes, it is worth noting that the color palette is not as jarring as it might be. Dubuffet was at least cautiously mindful of the need for success.

Dubuffet’s heady experience in the country and rejection of art education is evident in this painting. The heavily textured surface depicts a cow, rendered in the childlike innocence of patients held in psychological facilities. The uninhibited, savage approach to the canvas exemplifies the concepts of what Dubuffet termed Art Brut — the image seems entirely unschooled in the traditions of landscape. The image is thus at odds with the notions of «high art,» and approaches art making from the direction of artistic purity uninfluenced by cultural advancement. Going a step further, Dubuffet suggests how «cultural» and «savage» approaches to art together work to reaffirm civilization as a whole.

More Important Art

View all Important Art

Література[ред. | ред. код]

Тексти Дюбюфферед. | ред. код

- Jean Dubuffet, Prospectus et tous écrits suivants, Tome I, II, Paris 1967; Tome III, IV, Gallimard: Paris 1995

- Asphyxiante culture, Paris, Jean-Jacques Pauvert éditeur, 1968

- L’Homme du commun à l’ouvrage, Paris, Gallimard, 1973 Collection Idées

- Bâtons rompus, Paris, Editions de Minuit, 1986

Catalogue des travaux de Jean Dubuffet — Fascicules I-XXXVIII, Paris, 1965-1991 (з каталогом можна ознайомитися в Центрі Жоржа Помпіду, Париж)

Webel, Sophie, L’Œuvre gravé et les livres illustrés par Jean Dubuffet. Catalogue raisonné. Lebon: Paris 1991

Загальна літератураред. | ред. код

- Ragon M. Dubuffet. New York: Grove Press, 1959

- Selz P. The Work of Jean Dubuffet New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1962

- Loreau M. Jean Dubuffet, délits déportements lieux de haut jeu. Paris: Weber, 1971

- Franzke A. Jean Dubuffet, Basel: Beyeler, 1976

- Thévoz M. Art brut. New York: Rizzoli, 1976

- Thévoz M. Jean Dubuffet, Genève: Albert Skira, 1986

- Glimcher M. Jean Dubuffet: Towards an Alternative Reality. New York: Pace Gallery, 1987

- Webel S. L’œuvre gravé et les livres illustrés par Jean Dubuffet: catalogue raisonné. Paris: Baudoin-Lebon, 1991

- Haas M. Jean Dubuffet, Berlin: Reimer, 1997

- Lageira J. Jean Dubuffet, le monde de l’hourloupe. Paris: Gallimard; Centre Pompidou, 2001

- Danchin L. Jean Dubuffet. New York: Vilo International, 2001

- Bonnefoi G. Jean Dubuffet. Caylus: Association mouvements, 2002

- Jean Dubuffet: Trace of an Adventure / Ed. by Agnes Husslein-Arco. Muenchen: Prestel, 2003

- Krajewski M. Jean Dubuffet. Studien zu seinem Fruehwerk und zur Vorgeschichte des Art brut. Osnabrueck: Der andere Verlag, 2004

- Jacobi M. Jean Dubuffet et la fabrique du titre. Paris: CNRS, 2006

ТВОРЧЕСТВО

Ранние работы Дюбюффе (рисунки, портреты, этюды, 1920-1936), показывают острый графизм, скрывающий банальности внешнего вида.

Этот сорокалетний самоучка уже первой своей выставкой (1944, гал. Друэн на Вандомской площади) начал обновлять фигуративный словарь, глядя на жизнь неожиданным взглядом простодушного варвара («Мироболюс», «Мадам и Си», «От-Пат»). Дикий, разрушительный пыл художника сохранял, однако, парадоксальную целостность и высокое напряжение («Фотрие с пауком на лбу»).

Все произведения написаны в коричневых тонах, за исключением яркого колорита полотен, исполненных в Сахаре (в Эль-Голеа, где художник был трижды в 1947- 1949). Но эта живопись требовала также и обновления техники; художник использовал необычные, неблагородные материалы (застывшее смазочное сало, гравий) и различные смеси (живопись лаком и маслом)

Внимание, которое он уделял натуральности фактуры (старые стены, старые дороги, ржавчина, гнилье), ведет Дюбюффе к составлению странных пейзажей, «ментально» или «текстурологически» чистых, однотонных и плотных, насыщенных материей («Почвы и земли», 1952; «Взбитое тесто», 1953), на которой отпечатаны рудиментные знаки — следы человеческого присутствия

Трогательные «Маленькие статуи ненадежной жизни» (1954), где смешиваются шлак, обрывки губки, старая газета и тампон Jex, провоцируют на поиски аналогов, как и в «ассамбляжах отпечатков» (начиная с «Маленьких картин из крыльев бабочек», 1953). По словам самого Дюбюффе, в ситуации «празднования» окаменевших свидетелей с дикими жестами его удивляют очертания утесов и пыль листьев.

Пребывание в Оверни (лето 1954) положило начало серии этюдов коров, в которой спокойствие, присущее этому сюжету, заменено гротескным и беспокойным волнением. После периода литографических поисков («Феномены», 1958), Дюбюффе обращается к теме, которая до сих пор не была особенно популярна у художников — «Бороды», которые он воспевает с мягкой ностальгией («Бородатый цветок», 1960, рисунок китайской тушью; потом — гуашь и рисунки, названные «Ты сорвал бородатый цветок?»). Наряду с этой озадачивающей и живой плодовитостью, источниками или, по крайней мере, путями выражения стали выставки «брутального искусства» в Париже (первая прошла в 1949). Дюбюффе обращался к самым разным темам: детский рисунок (несмотря на то, что он творил для наставления подростков), анонимные надписи на облупленных стенах, шутовские непристойные каракули, выражающие смутную ностальгию, на стенах общественных туалетов или публичных бань, достоверно наивное творчество невольного художника (каменщика, парикмахера, столяра), который пишет, рисует, лепит, потому что… таково творчество всех сумасшедших.

Знаменательно, что источниками одного из наиболее цельных и обдуманных начинаний современного искусства были подобные работы, свидетельствующие в пользу того «дикого» зрения, которое было замечательно описано Андре Бретоном (1928).

В цикле «Урлуп» речь идет о формообразовании, по-видимому, более рациональном, чем прежде; выразительность уступает свое место пестрой головоломке, состоящей из знакомых мотивов (лестниц, кафетериев, персонажей с собаками, велосипедов)

Эту же эстетику художник затем применил в архитектурных проектах, непринужденно порывающих с рационализмом, всегда в той или иной степени присущей этому виду искусства, а также в скульптурах («Ведро важности», 1967, Нью-Йорк, музей Соломона Гуггенхейма; «Дон Кукубазар», 1972-1973). Основными циклами последних лет жизни Дюбюффе являются «Театры памяти» (1975-1978) составленные из частей старых произведений искусства в «Психо-городе» (1981-1982) персонажи изолированы в раскрашенном пространстве «Мишени» (1948) — почти абстрактное произведение из голубых и красных линий на белом и желтом фоне, и, наконец, «He-места», выставленные в 1985 в Центре Помпиду

Поэтичный и остроумный писатель, Дюбюффе сам дал своему методу лучший комментарий («Мемуар о развитии моих работ с 1952» в серии «Ретроспектива Жана Дюбюффе», Париж, 1960-1961), написанной в ироничном и всегда подкупающе точном стиле.

Литература

- Ragon M. Dubuffet. — N. Y.: Grove Press, 1959.

- Selz P. The Work of Jean Dubuffet. — N. Y.: The Museum of Modern Art, 1962.

- Loreau M. Jean Dubuffet, délits déportements lieux de haut jeu. — P.: Weber, 1971.

- Franzke A. Jean Dubuffet. — Basel: Beyeler, 1976.

- Thévoz M. Art brut. — N. Y.: Rizzoli, 1976.

- Thévoz M. Jean Dubuffet. — Genève: Albert Skira, 1986.

- Glimcher M. Jean Dubuffet: Towards an Alternative Reality. — N. Y.: Pace Gallery, 1987.

- Webel S. L’œuvre gravé et les livres illustrés par Jean Dubuffet: catalogue raisonné. — P.: Baudoin-Lebon, 1991.

- Haas M. Jean Dubuffet. — B.: Reimer, 1997.

- Lageira J. Jean Dubuffet, le monde de l’hourloupe. — P.: Gallimard; Centre Pompidou, 2001.

- Danchin L. Jean Dubuffet. — N. Y.: Vilo International, 2001.

- Bonnefoi G. Jean Dubuffet. Caylus: Association mouvements, 2002.

- Jean Dubuffet. Trace of an Adventure/ Ed. by Agnes Husslein-Arco. — Münch.: Prestel, 2003.

- Krajewski M. Jean Dubuffet. Studien zu seinem Fruehwerk und zur Vorgeschichte des Art brut. — Osnabrück: Der andere Verlag, 2004.

- Jacobi M. Jean Dubuffet et la fabrique du titre. — P.: CNRS, 2006.

Литература[править | править код]

- Ragon M. Dubuffet. — N. Y.: Grove Press, 1959.

- Selz P. The Work of Jean Dubuffet. — N. Y.: The Museum of Modern Art, 1962.

- Loreau M. Jean Dubuffet, délits déportements lieux de haut jeu. — P.: Weber, 1971.

- Franzke A. Jean Dubuffet. — Basel: Beyeler, 1976.

- Thévoz M. Art brut. — N. Y.: Rizzoli, 1976.

- Thévoz M. Jean Dubuffet. — Genève: Albert Skira, 1986.

- Glimcher M. Jean Dubuffet: Towards an Alternative Reality. — N. Y.: Pace Gallery, 1987.

- Webel S. L’œuvre gravé et les livres illustrés par Jean Dubuffet: catalogue raisonné. — P.: Baudoin-Lebon, 1991.

- Haas M. Jean Dubuffet. — B.: Reimer, 1997.

- Lageira J. Jean Dubuffet, le monde de l’hourloupe. — P.: Gallimard; Centre Pompidou, 2001.

- Danchin L. Jean Dubuffet. — N. Y.: Vilo International, 2001.

- Bonnefoi G. Jean Dubuffet. Caylus: Association mouvements, 2002.

- Jean Dubuffet. Trace of an Adventure/ Ed. by Agnes Husslein-Arco. — Münch.: Prestel, 2003.

- Krajewski M. Jean Dubuffet. Studien zu seinem Fruehwerk und zur Vorgeschichte des Art brut. — Osnabrück: Der andere Verlag, 2004.

- Jacobi M. Jean Dubuffet et la fabrique du titre. — P.: CNRS, 2006.

Artistic style

Dubuffet’s art primarily features the resourceful exploitation of unorthodox materials. Many of Dubuffet’s works are painted in oil paint using an impasto thickened by materials such as sand, tar and straw, giving the work an unusually textured surface. Dubuffet was the first artist to use this type of thickened paste, called bitumen. Additionally, in his earlier paintings, Dubuffet dismissed the concept of perspective in favor of a more direct, two-dimensional presentation of space. Instead, Dubuffet created the illusion of perspective by crudely overlapping objects within the picture plane. This method most directly contributed to the cramped effect of his works.

From 1962 he produced a series of works in which he limited himself to the colours red, white, black, and blue. Towards the end of the 1960s he turned increasingly to sculpture, producing works in polystyrene which he then painted with vinyl paint.

Accomplishments

- Dubuffet was launched to success with a series of exhibitions that opposed the prevailing mood of post-war Paris and consequently sparked enormous scandal. While the public looked for a redemptive art and a restoration of old values, Dubuffet confronted them with childlike images that satirized the conventional genres of high art. And while the public looked for beauty, he gave them pictures with coarse textures and drab colors, which critics likened to dirt and excrement.

- The emphasis on texture and materiality in Dubuffet’s paintings might be read as an insistence on the real. In the aftermath of the war, it represented an appeal to acknowledge humanity’s failings and begin again from the ground — literally the soil — up.

- Dubuffet’s Hourloupe style developed from a chance doodle while he was on the telephone. The basis of it was a tangle of clean black lines that forms cells, which are sometimes filled with unmixed color. He believed the style evoked the manner in which objects appear in the mind. This contrast between physical and mental representation later encouraged him to use the approach to create sculpture.

Early work

Jean Dubuffet, 1960.

In 1942, Dubuffet decided to devote himself again to art. He often chose subjects for his works from everyday life, such as people sitting in the Paris Métro or walking in the country. Dubuffet painted with strong, unbroken colors, recalling the palette of Fauvism, as well as the Brucke painters, with their juxtaposing and discordant patches of color. Many of his works featured an individual or individuals placed in a very cramped space, which had a distinct psychological impact on viewers. In 1943, the writer George Limbour, a friend of Dubuffet from childhood, took Jean Paulhan to the artist’s studio. Dubuffet’s work at that time was unknown. Paulhan was impressed and the meeting proved to be a turning point for Dubuffet. His first solo show came in October 1944, at the Galerie Rene Drouin in Paris. This marked Dubuffet’s third attempt to become an established artist.

In 1945, Dubuffet attended and was strongly impressed by a show in Paris of Jean Fautrier’s paintings in which he recognized meaningful art which expressed directly and purely the depth of a person. Emulating Fautrier, Dubuffet started to use thick oil paint mixed with materials such as mud, sand, coal dust, pebbles, pieces of glass, string, straw, plaster, gravel, cement, and tar. This allowed him to abandon the traditional method of applying oil paint to canvas with a brush; instead, Dubuffet created a paste into which he could create physical marks, such as scratches and slash marks. The impasto technique of mixing and applying paint was best manifested in Dubuffet’s series ‘Hautes Pâtes’ or Thick Impastoes, which he exhibited at his second major exhibition, entitled Microbolus Macadam & Cie/Hautes Pates in 1946 at the Galérie René Drouin. His use of crude materials and the irony that he infused into many of his works incited a significant amount of backlash from critics, who accused Dubuffet of ‘anarchy’ and ‘scraping the dustbin’. He did receive some positive feedback as well—Clement Greenberg took notice of Dubuffet’s work and wrote that ‘rom a distance, Dubuffet seems the most original painter to have come out of the School of Paris since Miro…’ Greenberg went on to say that ‘Dubuffet is perhaps the one new painter of real importance to have appeared on the scene in Paris in the last decade.’ Indeed, Dubuffet was very prolific in the United States in the year following his first exhibition in New York (1951).

After 1946, Dubuffet started a series of portraits, with his own friends Henri Michaux, Francis Ponge, George Limbour, Jean Paulhan and Pierre Matisse serving as ‘models’. He painted these portraits in the same thick materials, and in a manner deliberately anti-psychological and anti-personal, as Dubuffet expressed himself. A few years later he approached the surrealist group in 1948, then the College of Pataphysique in 1954. He was friendly with the French playwright, actor and theater director Antonin Artaud, he admired and supported the writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline and was strongly connected with the artistic circle around the surrealist André Masson. In 1944 he started an important relationship with the resistance-fighter and French writer, publisher, Jean Paulhan who was also strongly fighting against ‘intellectual terrorism’, as he called it.

БИБЛИОГРАФИЯ

- Ragon M. Dubuffet. New York: Grove Press, 1959

- Selz P. The Work of Jean Dubuffet New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1962

- Loreau M. Jean Dubuffet, délits déportements lieux de haut jeu. Paris: Weber, 1971

- Franzke A. Jean Dubuffet, Basel: Beyeler, 1976

- Thévoz M. Art brut. New York: Rizzoli, 1976

- Thévoz M. Jean Dubuffet, Genève: Albert Skira, 1986

- Glimcher M. Jean Dubuffet: Towards an Alternative Reality. New York: Pace Gallery, 1987

- Webel S. L’œuvre gravé et les livres illustrés par Jean Dubuffet: catalogue raisonné. Paris: Baudoin-Lebon, 1991

- Haas M. Jean Dubuffet, Berlin: Reimer, 1997

- Lageira J. Jean Dubuffet, le monde de l’hourloupe. Paris: Gallimard; Centre Pompidou, 2001

- Danchin L. Jean Dubuffet. New York: Vilo International, 2001

- Bonnefoi G. Jean Dubuffet. Caylus: Association mouvements, 2002

- Jean Dubuffet: Trace of an Adventure/ Ed. by Agnes Husslein-Arco. Muenchen: Prestel, 2003

- Krajewski M. Jean Dubuffet. Studien zu seinem Fruehwerk und zur Vorgeschichte des Art brut. Osnabrueck: Der andere Verlag, 2004

- Jacobi M. Jean Dubuffet et la fabrique du titre. Paris: CNRS, 2006

При написании этой статьи были использованы материалы таких сайтов: ru.wikipedia.org, ,

Творчество. Свобода. Живопись.

Allpainters.ru создан людьми, искренне увлеченными миром творчества. Присоединяйтесь к нам!

Жан Дюбюффе: жизнь и творчество художникаПроголосуйте

Summary of Jean Dubuffet

Jean Dubuffet disliked authority from a very early age. He left home at 17, failed to complete his art education, and wavered for many years between painting and working in his father’s wine business. He would later be a successful propagandist, gaining notoriety for his attacks on conformism and mainstream culture, which he described as «asphyxiating.» He was attracted to the art of children and the mentally ill, and did much to promote their work, collecting it and promulgating the notion of Art Brut. His early work was influenced by that of outsiders, but it was also shaped by the interests in materiality that preoccupied many post-war French artists associated with the Art Informel movement. In the early 1960s, he developed a radically new, graphic style, which he called «Hourloupe,» and would deploy it on many important public commissions, but he remains best known for the thick textured and gritty surfaces of his pictures from the 1940s and ’50s.

БИОГРАФИЯ ХУДОЖНИКА

Жан Дюбюффе родился в Гавре в 1901 г. в семье богатого виноторговца. Он учился в гаврском лицее, но уже в 1916 поступает в Школу изящных искусств этого же города. Приехав в Париж в 1918, он на протяжении полугода учится в академии Жюлиана, а потом начинает работать самостоятельно. Склонный к литературе, музыке, иностранным языкам, Дюбюффе ищет свой путь и приходит к убеждению, что западное искусство гибнет от изобилия академических рекомендаций (такова, и в самом деле, была реакция послевоенной живописи на искусство начала века).

С 1925 он занимается коммерцией, а в 1930 поселяется в Берси. И лишь в 1933 Дюбюффе вновь обращается к живописи. Спустя два года он создает марионеток и лепит маски по отпечатанным лицам. В 1937 художник во второй раз отказывается от живописи, и только спустя пять лет, окончательно выбирает карьеру художника.

В 1944 состоялась его первая персональная выставка в парижской галерее Р.Друэна. Сблизился с сюрреалистами. Стал основоположником Ар брют — «грубого» или «сырого» искусства, принципиально близкого к любительской живописи детей, самоучек, душевнобольных, не признающего общепринятых эстетических норм и использующего любые подручные материалы. В 1948 начал собирать коллекцию ар брют (в настоящее время находится в Лозанне).

В 1960 г. он работает над серией «Пари Сиркюс» — веселой пестрой хроники городской жизни со смешными названиями магазинов (выдуманных художником!), улицами, по которым снуют забавные человечки.

В 1962 г. Ж. Дюбюффе увлекается техникой спонтанно-бессознательного рисования шариковыми ручками, называя эти рисунки непереводимым неологизмом «hourloupe». Эти витиеватые, но скупые по цвету графизмы определили его позднее творчество. Все началось с игры: во время разговоров по телефону он набрасывает синей и красной шариковой ручкой странные фигуры, которые он затем вырезает и наклеивает на черную бумагу. Эти коллажи сопровождались забавными подписями на языке, придуманном Ж. Дюбюффе — непревзойденным мастером каламбура. Затем последовали объемные фигуры и предметы из полистирола. Следующий этап — ряд монументально-декоративных и архитектурных работ, наиболее известными из которых являются двадцатичетырехметровая «Башня со скульптурами», которая установлена в парке в парижском пригороде и клозери (оба памятника занесены в список исторических памятников), а также его собственная «Вилла Фальбала» (1971-1973), выстроенная в Периньи под Парижем из пластика (1 610 м?).

В стиле «hourloupe» был создан музыкальный театр «Куку Базар»: танцоры выступали здесь в масках среда фигур из полистирона, одетых Ж. Дюбюффе, с декорациями на колесиках. Первое из трех «исторических» представление этого живого театра было дано на ретроспективе в нью-йоркском Музее С.Гуггенхейма (1973). В Манхеттене Ж. Дюбюффе установливает четыре «Дерева-hourloupe». Тридцать семь частей декорации «Куку театра» были специально отреставрированы к выставке на средства фирмы Louis Vuitton-Moet-Hennessy.

В 1967 художник передал ряд своих произведений в Музей декоративного искусства в Париже. Работы Дюбюффе представлены также в Нац. музее современного искусства, Центре Помпиду в Париже, и в Музее современного искусства в Нью-Йорке.

За пять месяцев до смерти он прекращает рисовать и начинает работать над своей биографией «Биография быстрым шагом», которая станет последней книгой, вышедшей из-под пера Ж. Дюоюффе. Умер Дюбюффе в Париже 12 мая 1985 г. в возрасте 83 лет.

Литература

- Ragon M. Dubuffet. — N. Y.: Grove Press, 1959.

- Selz P. The Work of Jean Dubuffet. — N. Y.: The Museum of Modern Art, 1962.

- Loreau M. Jean Dubuffet, délits déportements lieux de haut jeu. — P.: Weber, 1971.

- Franzke A. Jean Dubuffet. — Basel: Beyeler, 1976.

- Thévoz M. Art brut. — N. Y.: Rizzoli, 1976.

- Thévoz M. Jean Dubuffet. — Genève: Albert Skira, 1986.

- Glimcher M. Jean Dubuffet: Towards an Alternative Reality. — N. Y.: Pace Gallery, 1987.

- Webel S. L’œuvre gravé et les livres illustrés par Jean Dubuffet: catalogue raisonné. — P.: Baudoin-Lebon, 1991.

- Haas M. Jean Dubuffet. — B.: Reimer, 1997.

- Lageira J. Jean Dubuffet, le monde de l’hourloupe. — P.: Gallimard; Centre Pompidou, 2001.

- Danchin L. Jean Dubuffet. — N. Y.: Vilo International, 2001.

- Bonnefoi G. Jean Dubuffet. Caylus: Association mouvements, 2002.

- Jean Dubuffet. Trace of an Adventure/ Ed. by Agnes Husslein-Arco. — Münch.: Prestel, 2003.

- Krajewski M. Jean Dubuffet. Studien zu seinem Fruehwerk und zur Vorgeschichte des Art brut. — Osnabrück: Der andere Verlag, 2004.

- Jacobi M. Jean Dubuffet et la fabrique du titre. — P.: CNRS, 2006.

Виставки[ред. | ред. код]

- 1944/45 Галерея Рене Друен (Galerie René Drouin), Париж

- 1947 Галерея П’єра Матісса (Pierre Matisse Galerie), Нью-Йорк

- 1954 Серкль Вольне (Cercle Volney), Париж

- 1957 Замок Морсбройх (Schloss Morsbroich), Леверкузен

- 1964 Виставка «L´Hourloupe», Палаццо Ґрассі (Palazzo Grassi), Венеція

- 1973 Музей Ґуґґенгайма (Guggenheim Museum), Нью-Йорк

- 1980 Академія мистецтв (Akademie der Künste), Берлін

- 1980 Музей сучасного мистецтва (Museum Moderner Kunst), Відень

- 1980 Виставковий зал Йозефа Гаубріха (Joseph-Haubrich Kunsthalle), Кельн

- 1981 «Виставка до 80-річчя» Музей Ґуґґенгайма (Guggenheim Museum), Нью-Йорк

- 1985 Галерея Беєлер (Galerie Beyeler), Базель

- 1998 Галерея Карстен Греве (Galerie Karsten Greve), Кельн

- 2009 Виставковий зал Гіпо-Культурштифтунг (Kunsthalle der Hypo-Kulturstiftung), Мюнхен

- 2009 Галерея Беєлер (Galerie Beyeler), Базель

Selected bibliography

Catalogue Raisonné

- Catalogue des travaux de Jean Dubuffet, Fascicule I-XXXVIII, Pauvert: Paris, 1965–1991

- Webel, Sophie, L’Œuvre gravé et les livres illustrés par Jean Dubuffet. Catalogue raisonné. Lebon: Paris 1991

Writings

- Jean Dubuffet, Prospectus et tous écrits suivants, Tome I, II, Paris 1967; Tome III, IV, Gallimard: Paris 1995

- Jean Dubuffet, Asphyxiating Culture and other Writings. New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 1986ISBN 0-941423-09-3

Principal studies

- George Limbour, L’Art brut de Jean Dubuffet (Tableau bon levain à vous de cuire la pâte), Paris, Éditions Galerie René Drouin, 1953.

- Michel Ragon, Dubuffet, New York: Grove Press, 1959 (Translated from French by Haakon Chevalier.)OCLC

- Peter Selz, The Work of Jean Dubuffet, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1962

- Max Loreau, Jean Dubuffet, délits déportements lieux de haut jeu, Paris: Weber, 1971

- Andreas Franzke, Jean Dubuffet, Basel: Beyeler, 1976 (Translated from German by Joachim Neugröschel.)OCLC

- Andreas Franzke, Jean Dubuffet, New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. 1981 (Translated from German by Erich Wolf.)ISBN 0-81090-815-8

- Michel Thévoz, Jean Dubuffet, Geneva: Albert Skira, 1986

- Mildred Glimcher, Jean Dubuffet: Towards an Alternative Reality. New York: Pace Gallery 1987ISBN 0-89659-782-2

- Mechthild Haas, Jean Dubuffet, Berlin: Reimer, 1997 (German)ISBN 3-49601-176-9

- Jean Dubuffet, Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 2001ISBN 2-84426-093-4

- Laurent Danchin, Jean Dubuffet, New York: Vilo International, 2001ISBN 2-87939-240-3

- Jean Dubuffet: Trace of an Adventure, ed. by Agnes Husslein-Arco, Munich: Prestel, 2003ISBN 3-7913-2998-7

- Michael Krajewski, Jean Dubuffet. Studien zu seinem Fruehwerk und zur Vorgeschichte des Art brut, Osnabrueck: Der andere Verlag, 2004ISBN 3-89959-168-2

Біографія і творчість[ред. | ред. код]

Jean Dubuffet, 1960.

Дюбюффе. Емалевий сад, . Музей Креллер-Мюллер, Нідерланди

Син виноторговця. У сімнадцятирічному віці прибув до Парижа. Товаришував з Максом Жакобом, Жаном Поланом, Арманом Салакру. Прочитав монографію Ганса Принцгорна «Живопис душевнохворих» (), яка справила на нього глибоке враження. Розчарувався у своїх попередніх роботах, в році повернувся в Гавр, зайнявся родиннним бізнесом — виноторгівлею.

Після смерті Дюбюффе в 1985 році стали відомі його музичні експерименти з Асгером Йорном, а також письменницький доробок Дюбюффе. Жан Дюбюффе активно спілкувався з багатьма видатними письменниками: Клод Сімон, Жан Полан, Вітольд Гомбрович. З 1954 року Дюбюффе входив до «Колежу патафізики» (фр. Collège de Pataphysique).

Загалом художник створив близько 10 000 робіт, які зазвичай утворюють серії: «Жіночі тіла» (), «Маленькі картинки з крил метеликів» (), «Маленькі статуї ненадійним життя» (), «Феномени» (), «Урлуп» () та інші роботи Дюбюффе представлені у найбільших музеях світу (найбільша колекція в Європі належить Фонду Ланген).